SAN DIEGO — Each November, Jim Bartell returns to the last clear conversations he shared with his son, Ryan. “What Ryan wanted most at the end was to be present,” he reflects this month. Ryan died of stage-4 pancreatic cancer in 2018. The family’s fight to keep him alert and comfortable, without the heavy sedation that blunts final goodbyes, sparked California’s Compassionate Access to Medical Cannabis Act, widely known as Ryan’s Law.

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the deadliest malignancies in oncology, in part because it is often diagnosed late and responds poorly to treatment. As World Pancreatic Cancer Day approaches on November 20, 2025, advocacy groups like the Pancreatic Cancer Action Network and the Ryan’s Law Foundation ask the public to wear purple and illuminate landmarks to honor patients and push for earlier detection, research funding, and better end-of-life care.

For families facing terminal diagnoses today, the question is urgent: will hospitals allow carefully managed, non-smokable medical cannabis as a palliative option when clinicians and patients agree it may help?

What Ryan’s Law does and doesn’t

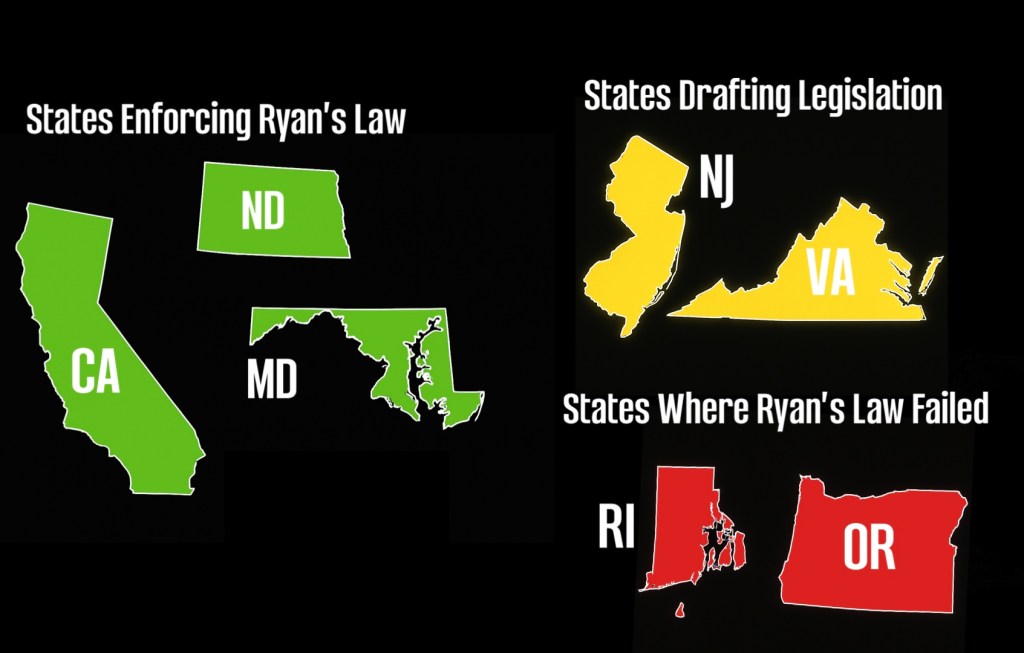

Enacted in California and since adopted in Maryland and North Dakota, Ryan’s Law permits medical cannabis for terminally ill patients inside licensed health-care facilities that choose to participate, under documented orders and secure storage protocols. Hospitals retain discretion to opt out; smokable and vaporized products are prohibited. Efforts to pass similar laws in Oregon and Rhode Island stalled this year, while advocates in states including New Jersey and Virginia continue laying groundwork for 2025.

Supporters say the law fills a narrow but meaningful gap in palliative care. “This isn’t about ideology, it’s about patient dignity and clinical choice,” said Shelby Huffaker, chair of the San Diego chapter of Americans for Safe Access (ASA). “When a physician believes a non-inhaled cannabis tincture or capsule could reduce nausea, anxiety, or pain, and a patient wants to remain lucid for family time, policy shouldn’t stand in the way.”

Hospitals often cite federal status, diversion risk, and workflow complexity. Ryan’s Law answers with guardrails: documented orders, chain-of-custody, secure storage, and institution-defined procedures. “We work with nurses, pharmacists, and compliance teams every day,” Bartell added. “The logistics are solvable. What families can’t get back is time.”

A family’s experience, a policy model

As Ryan’s disease advanced, standard inpatient protocols left him heavily sedated. Outside the hospital, non-inhaled cannabis helped him regain enough clarity for meaningful conversations. That experience led Jim Bartell to champion legislation that would let hospitals, clinicians, and families make similar decisions together. “We’re not asking for special treatment,” he said. “We’re asking for compassion that keeps patients present when it matters most.”

How to get involved (November and beyond)

Find Local Events: Visit pancreatic cancer and patient-advocacy sites to locate rallies, education sessions, webinars, and memorial events in your area.

Participate in Challenges: Register for virtual efforts like Project Purple’s seasonal runs or month-long mileage goals (e.g., “100 Miles in November”) to raise funds and awareness.

Wear Purple: Show support on World Pancreatic Cancer Day (Nov. 20) and throughout November; share photos and patient stories to keep attention on the cause.

Light Up Purple: Ask local venues to illuminate buildings or displays; consider lighting your home or business to signal solidarity.

Join Online Communities: Connect with caregiver and patient forums to share resources, advocate for policy change, and support families navigating late-stage care.

Engage Your Hospital: If you’re a clinician or administrator, review Ryan’s Law frameworks and palliative-care protocols. If you’re a caregiver, ask your care team what’s possible under current policy.

Contact Lawmakers: In states without hospital access policies, urge legislators to review California, Maryland, and North Dakota’s models and convene clinicians, nurses, and patient advocates.

“Policy moves when lawmakers meet the families behind the statistics,” Huffaker said. “Ryan’s story reminds us that comfort and connection are fundamental parts of care.”

The broader November message

Awareness is purple lights and hashtags; action is the clinical path that gives patients dignity and comfort without sacrificing being conscious during their final days. This month, as landmarks glow in purple and communities gather, hospitals and statehouses should focus on matching symbolism with policy implementation. For Jim Bartell, the measure is simple: “If Ryan’s Law helps one more child be present with their family at the end, then that’s proof that the policy is working. Now let’s make sure every family has that chance.”

Leave a comment